Civic Hero Series: America’s 1st Epidemic & The Black Philadelphians Who Answered the Call

For our first installment of the Civic Heroes Series, we look at one of the first examples of Americans who understood the importance of volunteering and civic responsibility. It's 1793. The United States is barely four years old, with its shiny new capital set up in Philadelphia (Yup, Philadelphia, Washington, D.C. was still under construction). Life is bustling after years of war, the streets are busy, and the spirit of a young democracy is in the air, but a catastrophic yellow fever epidemic hits like a wrecking ball. It breaks out in August, and for three long, terrifying months, Philadelphia is in chaos. Over 20,000 people flee, about 5,000 die, and countless others are left sick, scared, and struggling.

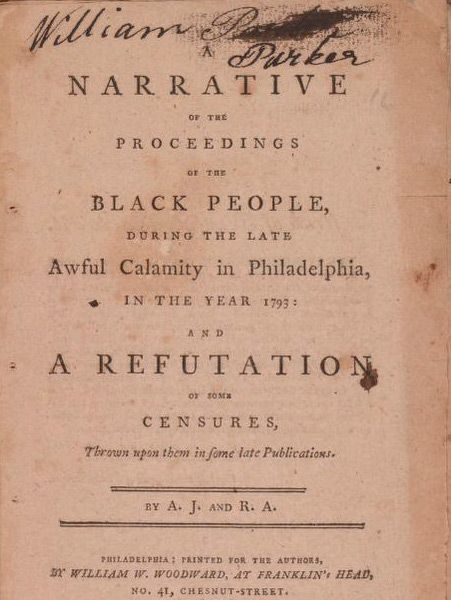

*Image: Absalom Jones and Richard Allen, "A Narrative of the Proceedings of the Black People, During the Late Awful Calamity in Philadelphia," 1794. (Rare Books and Special Collections, Library of Congress)

Civic Responsibility in Action

At the time, nobody knew what caused the disease. However, we now know mosquitoes bred exponentially due to the city's unsanitary living conditions in densely populated immigrant areas. There was no cure, no treatment, just fear and desperation. Doctors prescribed toxic cocktails, wine, and blood-letting to treat patients; these "cures" were often health risks in their own right. The only thing that slowed the epidemic was the arrival of cold weather, ending the mosquito's rapid reproduction.

In the face of this disaster, Philadelphia needed heroes—not the cape-wearing kind, but real people willing to step up. Volunteers were desperately needed to nurse the sick, comfort the grieving, and even bury the dead. And guess who answered the call? The Black Philadelphia community led by two remarkable men Absalom Jones and Richard Allen.

Both Jones and Allen were formerly enslaved men who had fought for their freedom. Jones became an Episcopalian minister, while Allen went on to found the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church. Together, they co-led the Free African Society, a mutual aid organization of free Black citizens committed to helping those in need. Through this society, they rallied volunteers to care for the sick and dying—regardless of race.

A Frustrating Turn of Events

But here's where the story takes a frustrating turn. After the epidemic subsided, a publisher named Matthew Carey (who had conveniently fled the city during the crisis) wrote a pamphlet about the epidemic. Instead of praising the Black community's heroic efforts, he accused them of spreading the disease, charging outrageous fees, and even stealing from the dead. Yep—talk about a slap in the face.

Jones and Allen weren't about to let that slide. In early 1794, they fired back with their own pamphlet, A Narrative of the Proceedings of the Black People, During the Late Awful Calamity in Philadelphia. In it, they dismantled Carey's false claims with eyewitness accounts and hard evidence. They also highlighted countless acts of kindness and bravery performed by Black volunteers—naming names, sharing stories, and setting the record straight.

The result? The truth won out. Their community's reputation was restored, and when both men established their own churches later that year, they received widespread support—including from the White community. Jones and Allen continued to be spiritual, civic, and political leaders well into the 1800s, leaving behind legacies that still inspire us today.

So, Why Does This Matter Now?

Civic responsibility—stepping up when your community needs you—isn't just something from history books. It's part of who we are as Americans. This story shows that Black people have always been active participants in our democracy, not just through voting and activism but also through service, volunteering, and community leadership. Whether it's 1793 or today, democracy thrives when ordinary people do extraordinary things. And guess what? That includes YOU.

Are You Ready to Do Your Part?

If you're a teacher (or know one), we have a fantastic opportunity to bring this spirit of civic engagement into classrooms through The Benjamin Project. This program helps students connect with stories like Jones and Allen's, showing them that history isn't just about the past but our choices today.

Want to inspire the next generation of leaders? Bring The Benjamin Project to your school. Let's keep the spirit of civic responsibility alive and well. Democracy isn't just something we read about—it's something we preserve through our involvement in our community.

**Adapted From: Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. “Black Volunteers in the Nation’s First Epidemic, 1793.” Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, www.gilderlehrman.org/history-resources/spotlight-primary-source/black-volunteers-nations-first-epidemic-1793. Accessed 5 Feb. 2025.

Join us in supporting future initiatives that inspire students to engage more meaningfully in their schools and communities.

DONATE TODAY